Django signals are a great way of communicating between your apps. But they are often misused. Find out what signals are for, when to define your own, and when to avoid them.

Django provides a mechanism to send and receive messages between different parts of an application, called the ‘signal dispatcher’. I’ve seen signals used in most of the projects I’ve been involved in, sometimes for good, but sometimes for ill. At their worst, they impair readability, introduce unexpected side effects and turn the codebase into a particularly nasty plate of spaghetti. Indeed, I have heard it said more than once that ‘signals are evil’.

And yet still I use signals. In fact I think they’re great as long as they’re used for the right reasons. Here’s what I think those reasons are…

Signals basics

First, let’s go over the basics (with thanks to the official Django docs). There are two key concepts: the Signal and the Receiver.

Concept 1: The Signal

A Signal is an object corresponding to a particular event. For example, we might define the following signal to represent a pizza having finished cooking:

from django.dispatch import Signal

pizza_done = Signal(providing_args=["toppings", "size"])Signals can send messages. This is achieved by calling the send() method

on the signal instance (passing in a sender argument, along with the

arguments specified above):

class Pizza:

def mark_as_done(self, toppings, size):

...

pizza_done.send(sender=self.__class__, toppings=toppings, size=size)Concept 2: The Receiver

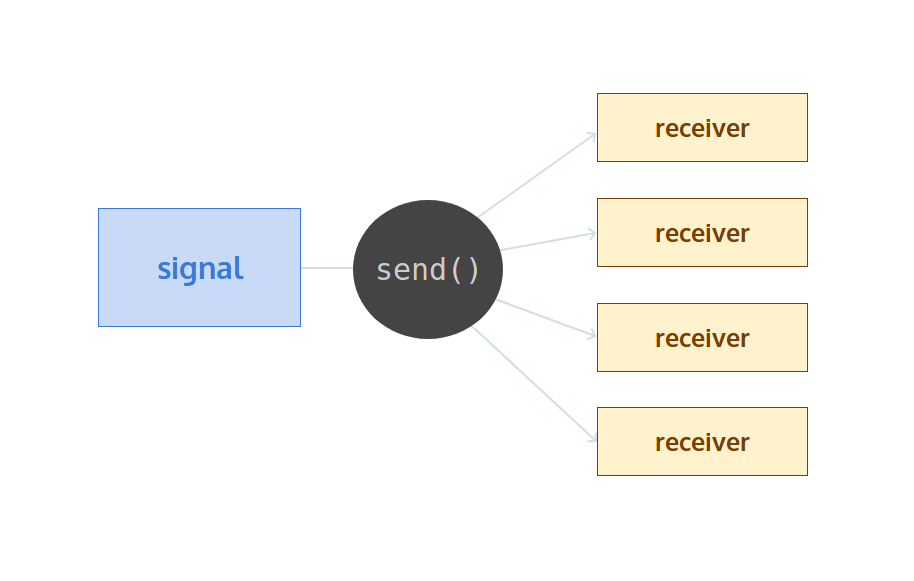

Receivers are callables that are connected to a particular signal.

When the signal sends its message, each connected receiver gets called.

Receivers’ function signatures should match what the

signal’s send() method uses. You connect a receiver to a signal using the

@receiver decorator:

from django.dispatch import receiver

from pizza import signals

@receiver(signals.pizza_done)

def turn_off_oven_when_pizza_done(sender, toppings, size, **kwargs):

# Turn off oven

...Those are the basics of the signals dispatcher. You have signals and receivers, the receivers can connect to the signals, and the signals send messages to any connected receivers:

The final thing to note is that signals are called synchronously; in other words, the normal program execution flow runs each receiver in turn before continuing with the code that sent the signal.

Tip

You must ensure the receiver code is imported when the project is

bootstrapped. I think the clearest place for this is in a receivers.py module,

which can be imported inside the

ready() method of the application configuration class.

If you follow this convention throughout your project, you may prefer to use

module autodiscovery in a single app, which will mean the receivers.py

module in every installed app will be imported:

# main/__init__.py

from django.apps import AppConfig as BaseAppConfig

from django.utils.module_loading import autodiscover_modules

class AppConfig(BaseAppConfig):

name = 'main'

def ready(self):

# Automatically import all receivers files

autodiscover_modules('receivers')

default_app_config = 'main.AppConfig'

An example

Let’s look at a practical example. Imagine we’re developing a ticket booking site. On this site, if an event is fully booked, users can join a waiting list.

We need to develop a feature where if someone cancels their booking, the system should kick off a process to allow those on the waiting list to book instead. To do this, the following function should be called when a booking is cancelled:

def promote_waiting_list(booking):

...We can achieve this using signals. First, we define a custom signal that represents the cancellation of a booking:

booking_cancelled = Signal(providing_args=['booking'])Next, we send the signal at the appropriate moment:

class Booking:

def cancel(self):

# Other logic

...

booking_cancelled.send(

sender=self.__class__,

booking=self,

)Finally, we define a receiver to kick start the waiting list process:

@receiver(booking_cancelled)

def promote_waiting_list_when_booking_cancelled(sender, booking, **kwargs):

promote_waiting_list(booking)A better way?

This all seems very well, but isn’t there a more straightforward solution? Why not just call the function directly from the cancel method like this:

class Booking:

def cancel(self):

...

promote_waiting_list(self)Much simpler and clearer. Surely, if all a signal dispatch does is call another function, it is needless complicating our code. Why, then, would we ever do this?

What signals are for

The signal dispatcher mechanism is not special to Django, but is actually a well known design pattern: the Observer pattern. The only difference is in terminology: in the Observer pattern a signal is known as a ‘subject’, and a receiver as an ‘observer’.

This pattern is used to decouple the observers (receivers) from the subject (signal). Indeed the Django docs tell us that signals “allow decoupled applications to get notified when actions occur elsewhere”.

But what exactly does ‘decoupled applications’ mean?

Project dependency flow

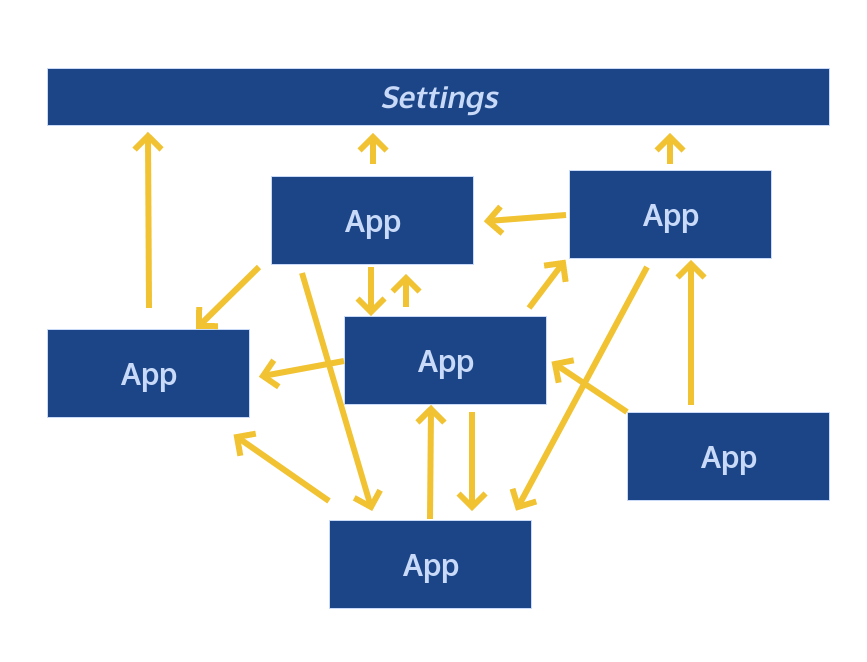

Here’s a Django project whose applications are coupled. The yellow arrows show which apps import things from each other.

The reason it’s tightly coupled is because there are circular dependencies between the apps, so you couldn’t remove one app without breaking the others. This is an antipattern, and should be avoided. (If you want to know more about this, see my Encapsulated Django talk.)

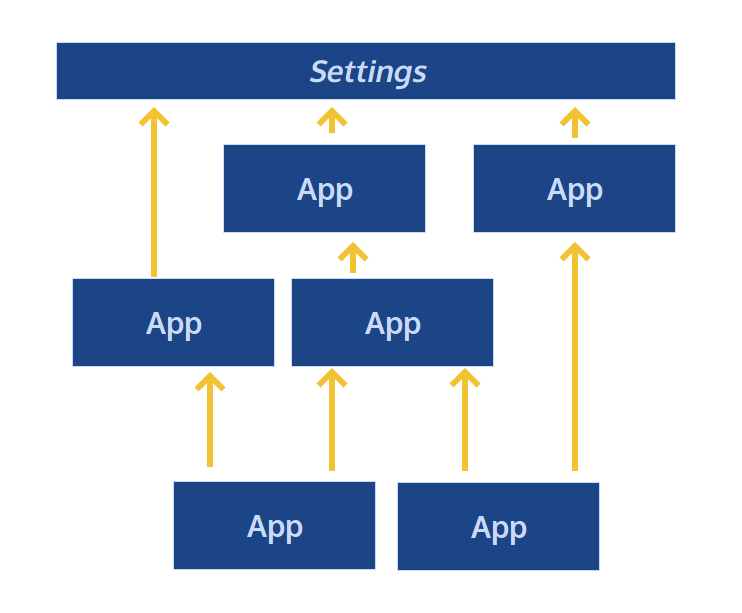

On the other hand, here’s a project where there is a single flow of dependencies:

This project is much better structured, but achieving a single flow is not always straightforward. Here’s where signals can help, and indeed what they are for.

The only reason to use signals

And now we come to the golden rule:

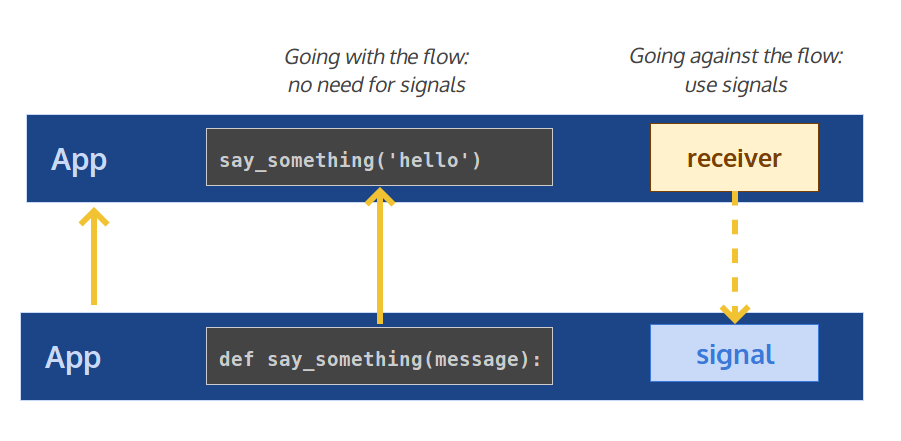

If you have two apps, and one app wants to trigger behaviour in an app it already knows about, don’t use signals. The app should just import the function it needs and call it directly.

Signals come into play if the reverse is needed: you want an app to trigger behaviour in an app that depends upon that app. In this case, signals are a great way of providing a ‘hook’ which the second app can exploit by connecting a receiver to it.

In conclusion

Going back to our event booking example, whether or not to use signals comes down to how we have chosen to architect our project.

In a less good design, bookings would know about waiting lists already. Since the two components are coupled together anyway, using signals would be a mistake. It wouldn’t actually decouple anything and would just make the code even harder to maintain.

In a better design, the core booking logic and waiting list logic would be separated. Bookings would live higher up the dependency chain, and be entirely ignorant of waiting lists. Using signals would allow a separate waiting list app to respond to the booking cancellation event, and kick off the processes needed to create the new bookings. This would be impossible with a straightforward function call. That would be a great use of signals.

Comments