Without a planned structure, larger Python projects can become a complicated web of interdependencies. The Rocky River is an architectural pattern to help make larger projects easier to work with.

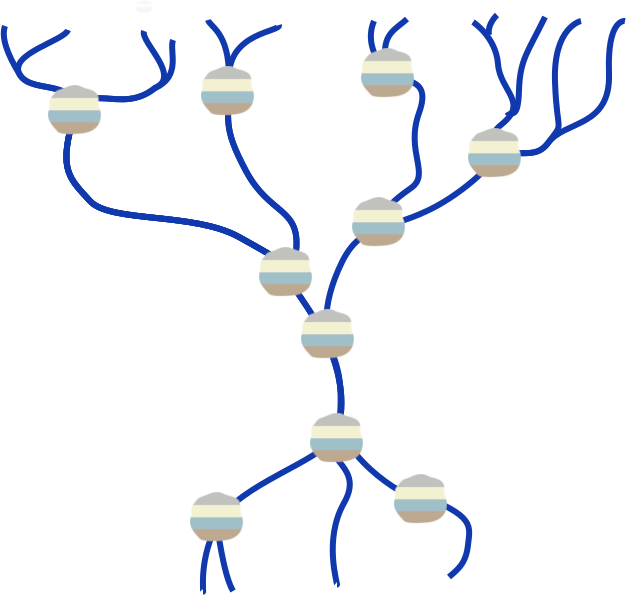

Imagine a river system, with many streams flowing together, and rocks dotted along the path of the water. Each of these rocks has a series of horizontal layers.

This is the ‘Rocky River’ architectural pattern, and it has three characteristics:

- Small components.

- Layers within the components.

- Dependencies only flow in one direction.

Let’s dig into the details of what these characteristics mean for a Python project.

1. Small components

Small rocks tend to be easier to work with than big ones. So it is with components in your software.

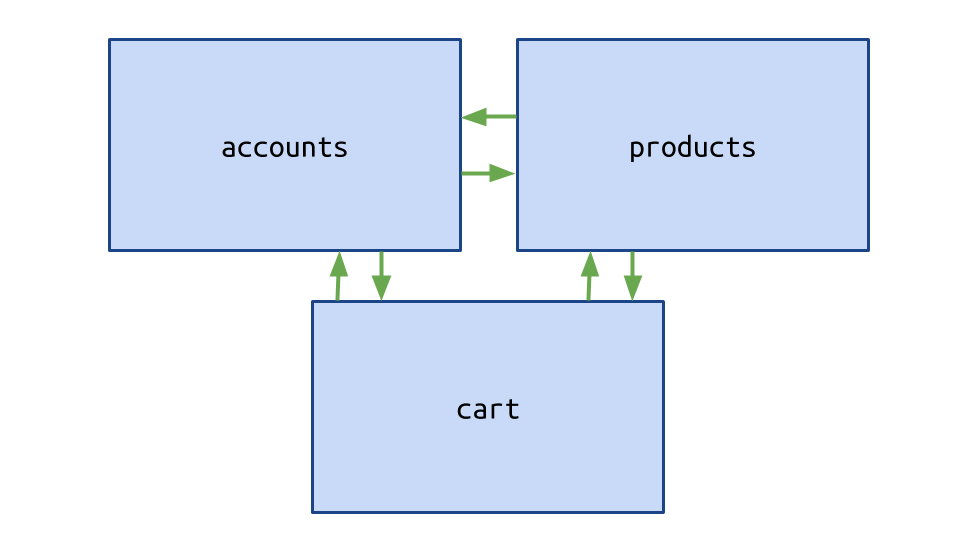

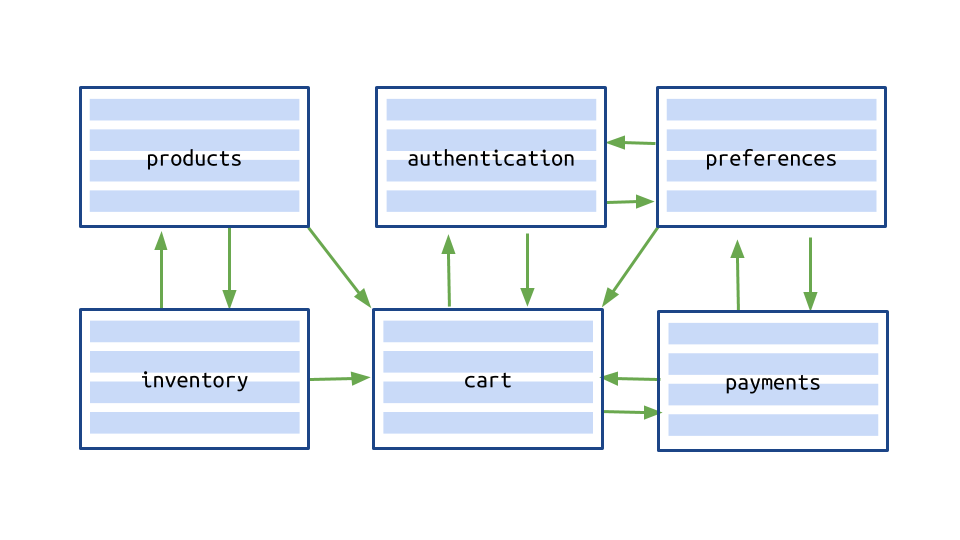

For example, an ecommerce site might have an accounts component, a products component and a shopping cart component. These components could be organized into three large subpackages within your code base. (The green arrows depict the imports between the packages.)

As new features are added, these subpackages tend to become unwieldy. You should look for opportunities to break them apart.

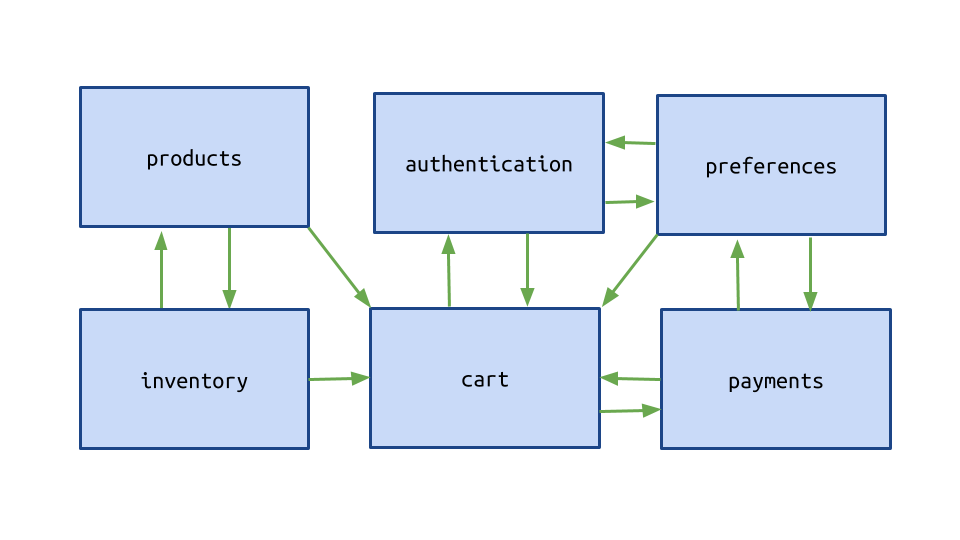

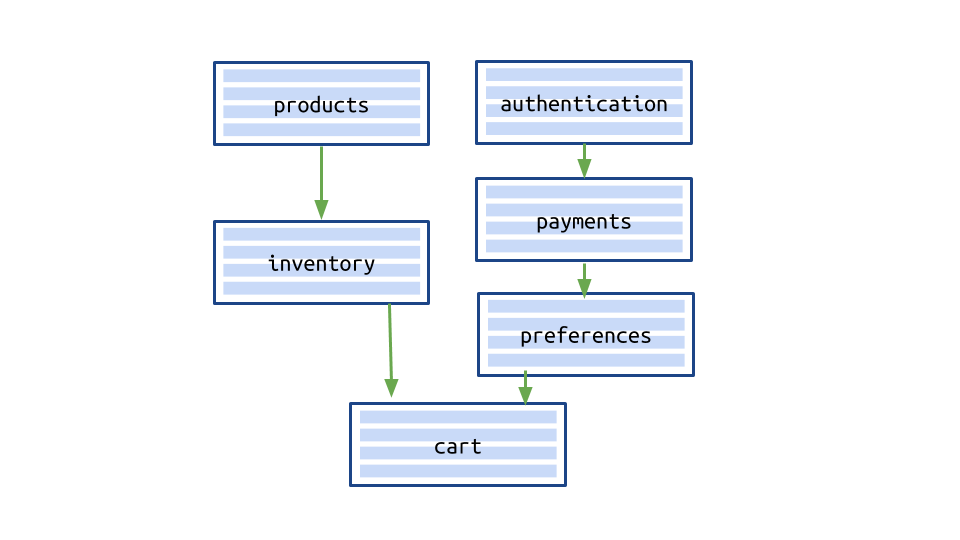

For example, accounts might be able to be broken up further into authentication and user preferences. Inventory management could be pulled out of products, and payments could be pulled out of the shopping cart. The application could look more like this:

In terms of file structure, there are two good options. Either use a flat structure:

project/

authentication/

preferences/

products/

inventory/

cart/

payments/

Or nest components within each other:

project/

accounts/

authentication/

preferences/

products/

main.py

inventory/

cart/

main.py

payments/

Breaking your project’s components apart like this makes them easier to understand, change and test. Exactly how small is, of course, a matter of judgement. While big is bad, you also don’t want too small: sand is harder to carry around than a handful of pebbles.

2. Layers within the components

Rock can be formed of layers. In the Rocky River, each component in your project should also be layered.

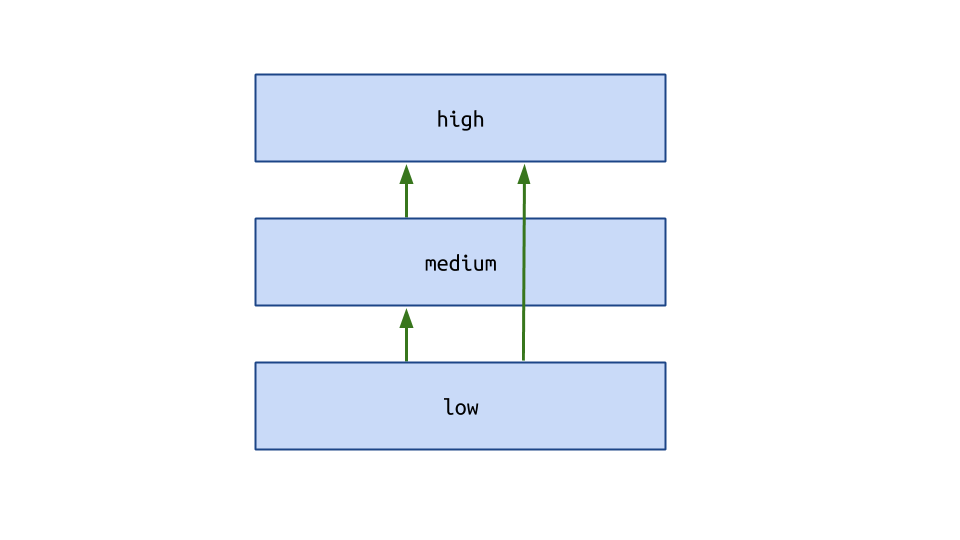

A layered architecture is a common pattern in software. In a nutshell, it involves structuring your code into sections stacked up on top of each other. These parts are called ‘layers’.

Every layer should be ignorant of any layer higher than it; however it may call any layers below it.

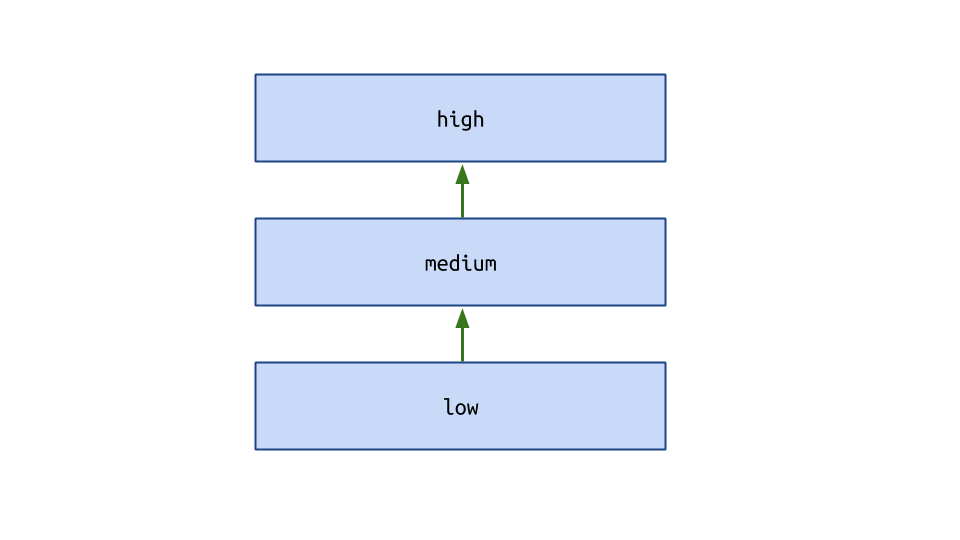

In a Python package, this could look like this:

mypackage/

__init__.py

high.py

medium.py

low.py

For a layered architecture to be followed:

lowmust not import any code frommediumorhigh.mediumcan importlowbut nothigh.highcan import from either of the others.

A more restrictive variation is ‘closed layers’, in which a layer may only call code in the layer immediately beneath it, as shown below.

In this case, high would not be allowed to import low.

In reality, of course, there might be more than three of them, and they would have more specific names. For example, in Django, a component might look something like this:

cart/

__init__.py

urls.py # Routes HTTP requests to views.

views.py # Validates the incoming request and delegates to the domain layer.

domain.py # Business logic.

models.py # Database storage layer.

You can choose your own way of breaking up the higher and lower level concerns: the important thing is to adhere to the dependency flow.

Continuing with our ecommerce example, the application would now be structured like this:

3. Dependencies only flow in one direction

The final characteristic of the Rocky River describes the relationship between the ‘layered rocks’ in your project. This is where the river comes in.

At any point along a river system, water may have come from many different upstream sources. However, it knows nothing of what is downstream. This should be the same for the components in your project.

You must decide a order of components, from upstream to downstream. Upstream components must never import from anything downstream.

In our ecommerce example, we now see the Rocky River structure take shape. Rather than many circular dependencies between the components, as in the earlier examples, there is now a directional flow.

Now we have a code base that has:

- Small components.

- Layers within the components.

- Dependencies that only flow in one direction.

That’s the pattern of the Rocky River. Sometimes you may find you need to work harder to obey the pattern, but in the long run you’ll find your project much easier to work with as it grows in complexity.

Appendix: The Rocky River in practice

Python enforces neither layers nor a wider dependency flow. This needn’t stop you following this pattern; you just need to commit to following the rules, and stick by them.

The simplest way to do this is just to document the dependency flow in a file or wiki. This could simply be in the form of a list that developers agree to adhere to:

# dependencies.txt

Module dependency flow, from upstream to downstream.

(Modules higher up in the list should not import those lower down.):

- products

- inventory

- authentication

- payments

- preferences

- cart

Alternatively, you could enforce the dependency flow using a tool such as Layer Linter.

Further information

- My talk on the Rocky River, which gives a lot more practical advice how to follow the pattern in a Django project.

- The Layers pattern in Chapter 2 of Pattern-Oriented Software Architecuture Vol. 1 (Buschmann, Meunier, Rohnert, Sommerlad and Stal, 1996).

- Layer Linter, a tool to help enforce this architecture.

- Practical advice on how to break Django apps apart, in Encapsulated Django.

Comments