Design is crucial to good software development, but many people lack a process for doing it. In this blog entry, I explain the three step process I use.

Let me ask you a question: how do you go about designing the software you build? What process, if any, do you follow?

Over the years, I’ve noticed that many of us developers understand the importance of design, but aren’t sure how to go about it. We may be aware of tools like design patterns and test driven development, but somehow that isn’t enough.

I’ve been reflecting recently on the design process that I use. If you’re someone who feels they are missing such a process, maybe you’ll find this one helpful.

Before we look at it, though, let’s consider for a moment a design process that is, I think, more commonly followed. Perhaps you’ll recognise it.

Code Driven Design

There is an approach to design that many, if not most, developers adopt unthinkingly. Let’s call it Code Driven Design. It’s the process we’re likely to follow automatically; the path of least resistance.

Code Driven Design is a development process where the primary activity is writing code. The driving force is to get a piece of functionality working, and we gradually feel our way towards the solution by changing the code.

If that sounds merely like a straightforward description of your working routine, then you’re probably using this process. I sometimes use it myself. It’s undoubtedly an explorative, creative process, and it often works well. But there are down sides to developing software in this way.

Down side #1: rushing to the finish line

The mindset of Code Driven Design often comes hand in hand with trying to finish something as quickly as possible. If we begin development of a feature by coding, it’s often borne out of a feeling that we need to ‘get on with it’.

Of course, delivering quickly is a great thing to aspire to, but software projects tend to be a longer term endeavour.

If we focus primarily on the quickest design, we miss opportunities for better design. Often a piece of functionality can be delivered rapidly by, say, adding an extra conditional or flag. But as a whole we may be adding unnecessary complexity to the software. If everyone is doing this all the time, our systems become harder and harder to work with. In all but the shortest time frames, it is more efficient to balance delivery times against design quality.

Down side #2: collaborating too late

Another risk that I see with this approach is that peer review - such an important part of improving software quality - comes much too late in the process.

Once we’ve gone to the trouble of writing a lot of working code, it’s very difficult to consider throwing it all away and tackling the problem in a different way - even if, in retrospect, everyone agrees it would have been better.

Down side #3: doing too many things at once

The biggest downside of Code Driven Design is that we’re trying to think about too many things at once.

If we design by coding, we’re likely to end up thinking about multiple things at the same time: not only how the code is factored, but also how the system is behaving and, even deeper, the fundamental concepts and assumptions at the heart of the software. By designing all of these things simultaneously, we run the risk of not giving each aspect the attention it deserves. All too often, software design becomes only code design: the other important questions are answered unthinkingly and without genuinely weighing up the options.

It’s easier to tackle these questions one at a time.

Model, Behaviour, Code

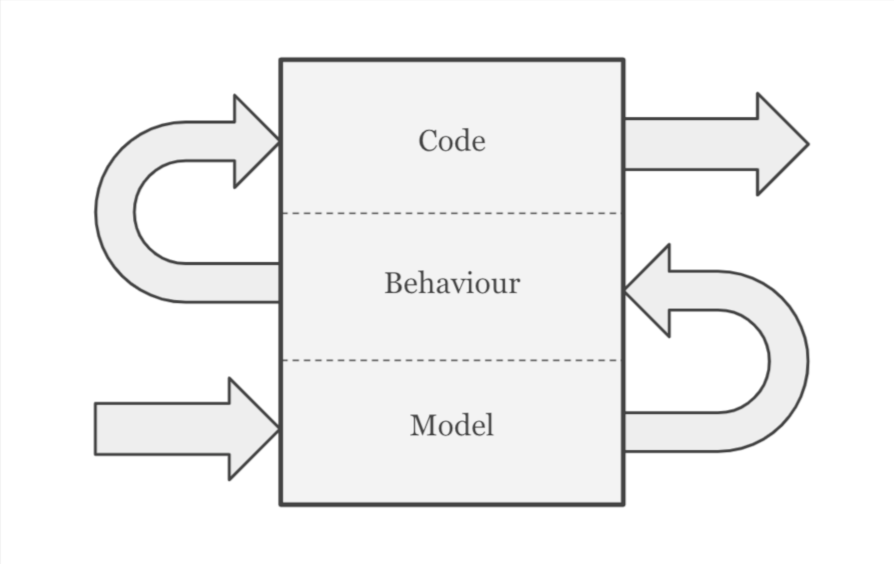

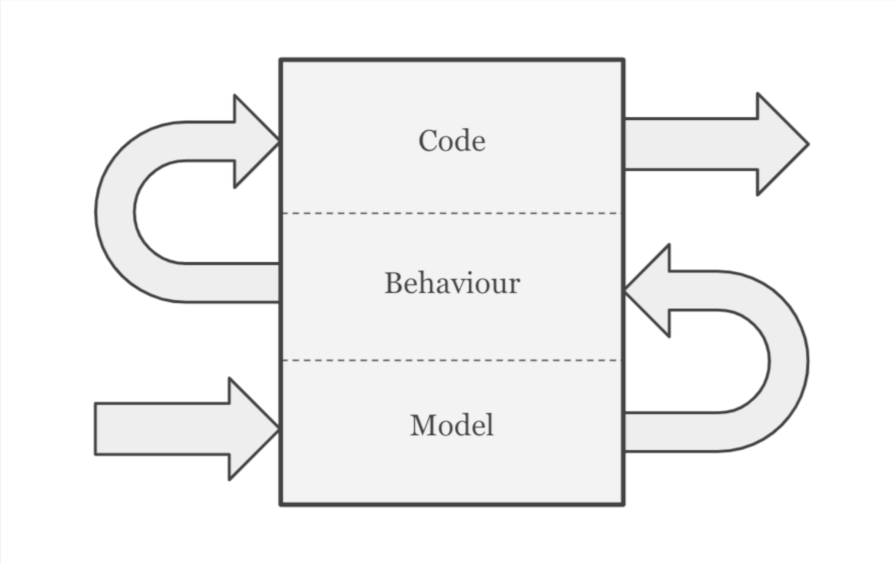

Here, then, is an alternative to Code Driven Design that I find helpful. It’s a three step process that I call Model, Behaviour, Code.

At its heart is the idea that the design of a piece of software can be thought of as a stack of three distinct concerns, each founded on the concern below it.

At the bottom of the stack is the Model, next is Behaviour, and at the top is the Code.

When I tackle a new piece of functionality, I start by designing the bottom of the stack, and work my way upwards. I don’t worry about things that belong higher up the stack until I’ve designed solid foundations for them to rest on. I seek feedback on each item in the stack before moving on to the next one.

So, my process begins by developing the model on which everything sits. Once this is in place, I move on to thinking about how the system behaves. Only once I understand both the system’s model and its behaviour do I begin thinking about the code.

Step One: Model Design

The model is the conceptual framework upon which our solution will be founded. This is where we start.

Typically, designing a model consists of defining the structure of that solution in a consistent language: the nouns, verbs and adjectives that will be used to talk about what the software does. A conceptual model can take many forms, but most typically it will feature data structures together with some higher level concepts.

By way of example, let’s look at Twitter. It features users who may follow each other. Any user may tweet to their followers. Each user has a personalized stream which lists the tweets of the users they are following. These central concepts are Twitter’s model.

Notice this model is a language for talking about what Twitter does. It’s not a database schema, nor is it a concrete specification for organizing language-specific details such functions, methods and classes. It is a non-technical, conceptual framework that the end users of the software will experience.

What form should a model take? Models are pure concepts, so it doesn’t need to be implemented anywhere in particular (at least not in this step). The important thing is that it’s coherent and well defined.

Having said that, it’s a great idea to work with others on designing the model, so you’ll probably need some way of externalising it. A common way to do this is using UML class diagrams, but if you do this, avoid addressing language-specific implementation details in this step. Make any diagrams as non-technical as you can: ideally you should be able to develop a model with someone who isn’t a developer but who has good understanding of the problem you’re trying to solve.

Modelling is a large subject which I can’t do justice to here, but a good place to go to gain further insight is Domain Driven Design, a software development approach centered around modelling. Begin by watching this video from Eric Evans.

Anyway, once we have a precise, coherent language to talk about the solution, possibly scribbled on the back of an envelope, we’re ready to move on to the next step.

Step Two: Behavioural design

Behavioural design is all about what, at a high level, the software actually does: the real world concerns of processes, networks, databases and the like. This is often referred to as ‘software architecture’, but because that term is also used to describe things like code organization, I’ve avoided it.

Let’s take an example of behavioural concerns from the world of web development: we are building a page which allows an admin to bulk create some users who can log into our website.

It’s easy to jump straight into building this, but there are actually several different decisions we need to make:

- How should the data be provided? As a text area that can be pasted in from a spreadsheet, or as a file upload? What format should the data be in?

- Should the entire import be performed during the user’s HTTP request, or should we process the import asynchronously?

- How should we handle invalid data? For example, should we fail the whole import, or just report on ones that were invalid?

- How should we handle unexpected errors? Should the entire import roll back, or should it commit as much as it can?

These are the kinds of questions we should be considering when designing the behaviour. They are nothing to do with how to organise the code, nor do they involve modelling: they’re practical concerns about how to deliver the solution. Usually in order to decide, we need to make trade offs: different options have different pros and cons.

Sometimes, once we begin to think about this behaviour, we’ll realise it doesn’t fit well with the model. If that’s the case, it may be worth revisiting the model so that it better supports the system’s behavioural needs.

Behavioural design is another huge subject. But whatever our technical expertise, just taking a moment to consciously consider how the system should behave (and review it with others) can save a lot of time down the line.

If you do want to improve your thinking in this area, I can highly recommend Designing Data-Intensive Applications by Martin Kleppman: it’s a rich and detailed catalogue of the technical decisions open to us, in particular relating to distributed systems and databases.

Step Three: Code Design

Once we have a good understanding of how the system will behave, and its underlying model, we’re in the position to start deciding how the code will be organized.

This is the realm of practices like design patterns, refactoring, clean coding and test driven development. Factoring code is a craft about which many books have been written - but it is made much easier if the fundamental modelling and behavioural questions have already been settled. In particular, our model gives us a language to talk about what we’re doing, which helps enormously with things like naming variables.

The importance of iteration

While designing in one layer of the stack, we’ll often realise a problem with the design of a layer below. That’s of course simply a matter of consciously going back and adjusting the design to reflect what we’ve learned.

I should also say that this process works best when the development is agile - that is, work commences on small, incremental deliverables (rather than ‘big bang’ releases). When initially given a feature, it’s helpful to break it down into smaller iterations. The model, behaviour and code can be redesigned each time.

In summary

I’ve found designing software in these three discrete steps enormously helpful. If you’re someone who habitually practices Code Driven Design, try Model, Behaviour, Code instead. You will get most benefit from it if you involve others (at least at review stage) in each step - not just all at the end.

If you’ve found this useful, or indeed use a different design process, then leave a comment. Good luck!

Comments